# Imagine we have a sample size of N participants

N = 1000

# Our latent unobservable variable, is a normally-distributed

# variable with mean 0 and sd 1

latent <- rnorm(N, 0, 1)On the predictive power of implicit measures of ratial attitudes

A commentary on Axt and colleagues (2025)

“Badly modeling latent factors undermines your results and misleads your conclusions.”

Incremental validity in the case of higher-order latent variables

During our Structural Equation Modeling course, we teach PhD students a simple but deceptively powerful fact about predictive validity in multiple regression. Imagine a single latent variable—call it racial attitudes—that predicts a behavioral outcome such as discriminatory behaviors. Now imagine that we have two different measures of this latent variable, for example an explicit self-report and an implicit reaction-time task.

Students often assume that if we regress the behavioral outcome on both the explicit and implicit measures simultaneously, the resulting regression coefficients tell us “which one is the better predictor”, but they also expect both effects will be zero because we are ‘controlling’ for the same thing. But both these intuitions are mistaken. If both measures load on the same underlying latent construct, then both will almost always be statistically significant in a large enough sample, even if neither has any unique predictive effect. The coefficients simply reflect their relative loadings on the same latent cause.

This is not a subtle point: it is a foundational implication of classical test theory and the logic of multiple regression. If we want to know whether either measure has incremental validity, we must first model and remove the influence of their common latent factor. Otherwise the incremental effect is an artifact of confounding.

Don’t believe it? Here is a quick simulation to prove the point.

We start by simulating our latent variable (racial attitudes):

We assume this latent variable to have an effect on Y (discriminatory behaviors). The unstandardized effect is 0.33:

# Our dependent variable is again a normally-distributed

# variable, partially explained by 'latent'

Y = .33*latent + rnorm(N, 0, 1)The latent variable and Y are now correlated around .30:

round(cor(latent,Y),2)[1] 0.32However, we cannot measure the latent variable directly. We need to build a questionnaire/test/paradigm that allows measuring and observing that construct. We build two of them, one explicit, with a higher loading, and one implicit, with a smaller loading. Let’s do it:

# Explicit is just regressed on the latent variable

# To have a higher loading we multiply latent by .8

explicit = .80*latent + rnorm(N,0,1)

# Impicit is the same, but with smaller loading (.5)

implicit = .50*latent + rnorm(N,0,1)We now have our data collection: we observed the dependent variable, and the two observed indicators of the latent variable [Note that none of them has any specific effect on Y!, We simulated it like this]. What happens if we test their multiple associations with Y?

Y=scale(Y);explicit=scale(explicit);implicit=scale(implicit)

fit <- lm(Y ~ explicit + implicit)

round(summary(fit)$coefficients,3) Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 0.000 0.031 0.000 1.000

explicit 0.191 0.032 5.919 0.000

implicit 0.101 0.032 3.135 0.002TWO SIGNIFICANT EFFECTS! Let’s publish it, we found incremental validity of explicit attitudes above and beyond implicit attitudes and viceversa!

The simulation illustrates the key point: significant regression coefficients by themselves do not establish incremental predictive power. They can easily emerge when both predictors share variance due to an underlying latent trait—even if there are no specific effects at all. This was nicely explained by Julia Rohrer in her October 2025 blogpost, and has been know since many years (e.g., Westfall and Yarkoni 2016).

But this is not just a didactic issue. It has immediate consequences for how we interpret claims about the predictive and incremental validity of implicit measures—including the recently published adversarial collaboration by Axt et al. (2025).

Reanalyzing Axt and colleagues’ dataset

The recent paper ‘On the relationship between indirect measures of Black vs. White racial attitudes and discriminatory outcomes: An adversarial collaboration using a sample of White Americans’ represents one of the largest and methodologically strongest empirical efforts in the history of implicit bias research. With over 2,100 White American participants, four implicit measures, four explicit measures, four behavioral tasks, and a preregistered SEM framework, it looks—at first glance—like the definitive test the field has been waiting for.

Their headline finding is clear:

Implicit attitudes predict discriminatory behavior, and they explain ~2.5% of the variance beyond explicit attitudes.

But here is the crucial problem: the model they fit assumes that implicit and explicit attitudes are separate causes of discriminatory behavior. The SEM explicitly excludes the possibility that both sets of indicators reflect a single underlying general attitude factor—an exremely plausible scenario in this case (Schimmack 2021) and exactly the scenario our simulation demonstrates.

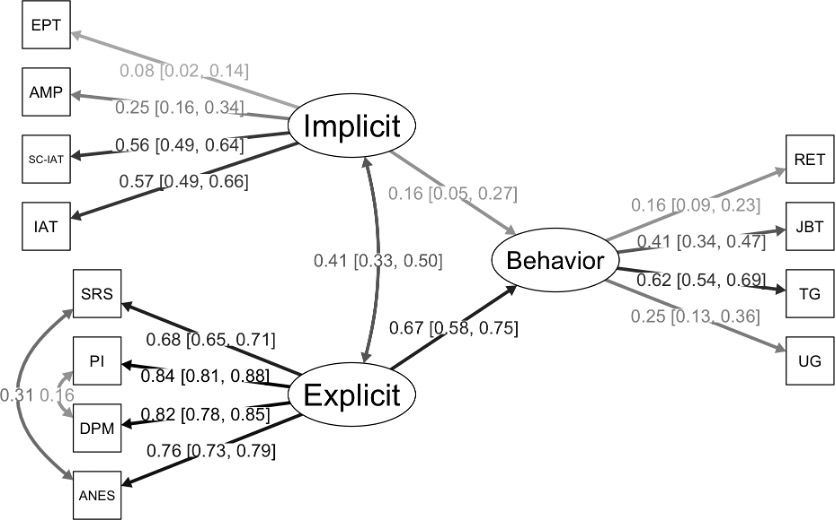

Indeed, the entire model in the published paper (see Figure 1 and the lavaan syntax below) implies that:

There is a latent implicit factor,

A separate latent explicit factor,

And both compete to predict latent discriminant behavior.

What is missing is the latent general racial attitude factor that would naturally give rise to shared variance across both implicit and explicit methods (which are highly correlated). If such a factor exists—and there are strong theoretical, empirical, and psychometric reasons to believe it does—then their incremental validity claim could collapse.

model_A <- '

# measurement model

implicit =~ iat + sciat + amp + ept

explicit =~ anes + dpm + pi + srs

discrim =~ ug + tg + jbt + ret

# paths

discrim ~ implicit + explicit

# residual correlations

anes ~~ srs

dpm ~~ pi

'So what happens if we add that general latent factor?

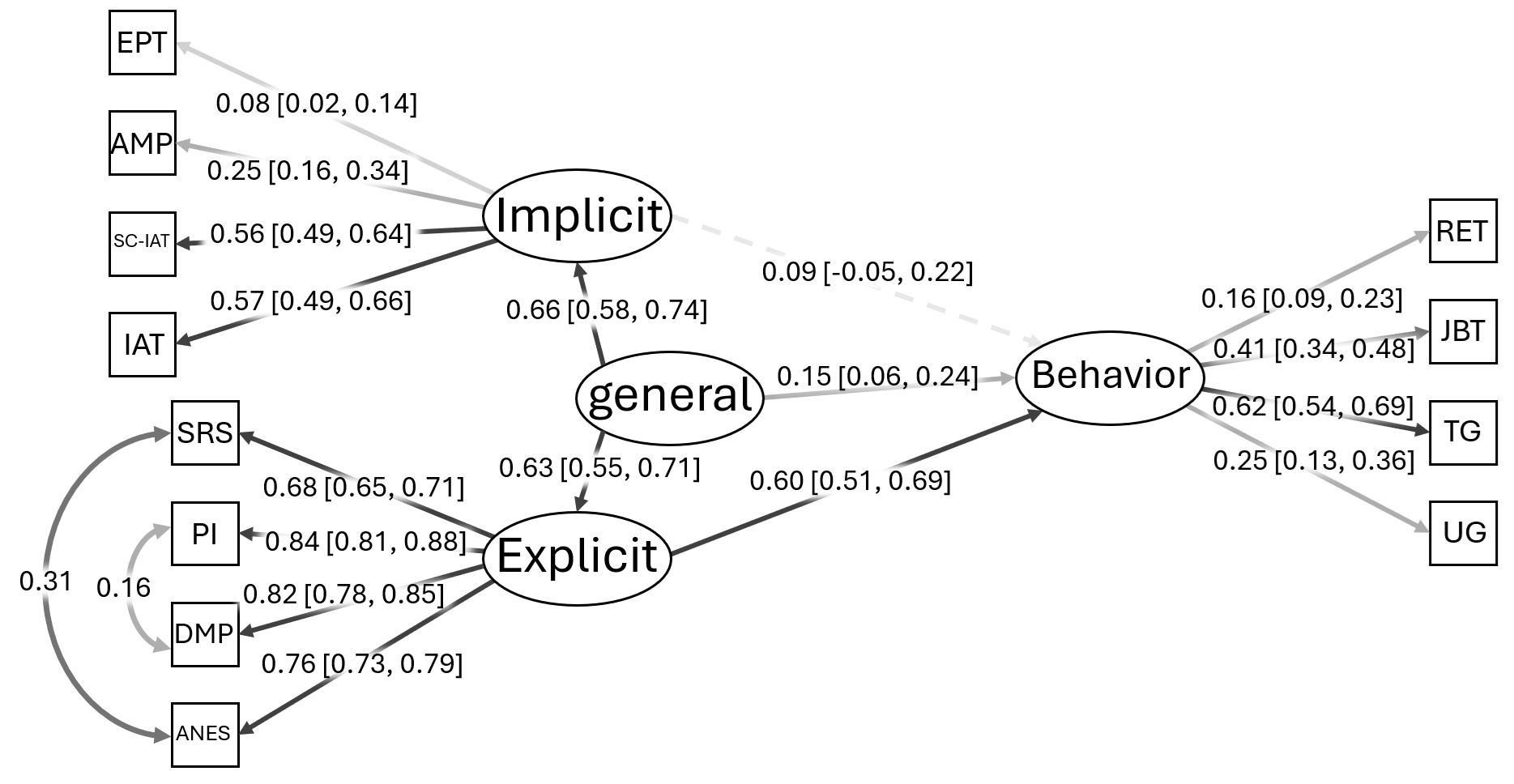

When we implement a hierarchical model—one general attitude factor plus the specific method factors—we get good fit (CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.03) but a radically different picture Figure 2:

The general attitude factor significantly predicts discriminatory behavior (β ≈ 0.15).

The explicit-specific factor still predicts behavior strongly (β ≈ 0.60).

The implicit-specific factor shows no meaningful unique relationship with discrimination (β ≈ .09, p = .23).

This is the model we should have tested from the beginning. And once we do, the “incremental validity” of implicit measures disappears.

model_A <- '

# measurement model

implicit =~ iat + sciat + amp + ept

explicit =~ anes + dpm + pi + srs

general =~ implicit + explicit

discrim =~ ug + tg + jbt + ret

# paths

discrim ~ implicit + explicit + general

# residual correlations

anes ~~ srs

dpm ~~ pi

'

What should we conclude?

Claims of incremental validity for implicit measures collapse once we correctly model the latent structure of attitudes.

This insight generalizes far beyond implicit bias research. Many fields routinely treat different methods as different constructs:

cognitive abilities vs. g,

specific anxiety subscales vs. general anxiety,

domain-specific “mindsets” vs. a general belief system

personality facets vs. general factors.

…

In all these cases, without modeling the well-known general factors, we risk misinterpreting trivial method-specific residuals as psychologically meaningful incremental predictors.

The lesson is simple but profound:

Before searching for incremental validity, model the common latent variable.

Otherwise you are not testing incremental validity at all.

Final Thoughts

Scientific progress requires modeling our constructs correctly. Without that foundation, even the largest samples and most elaborate collaborations cannot answer the question they set out to resolve.

Other readings

See also https://replicationindex.com/2025/12/02/is-the-implicit-association-test-too-big-to-fail/ for different perspectives.

Acknowledgment

A special thank to Enrico Toffalini who taught me most of these things.